Potential new target found for childhood kidney disease

An international research team from UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health (UCL GOS ICH), Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH), and the Hôpital Universitaire Necker‑Enfants Malades (Paris, France) have identified a new feature of a rare kidney disease in children that could help develop improved treatments.

Kidney disease is a condition in which the kidneys are damaged and can’t filter blood in the way they should. This damage can cause waste and fluid to build up in the body. Kidney disease can also cause other health problems such as cardiovascular disease. In children, kidney disease is rare but it can be extremely serious and require dialysis or eventual transplant.

Some children with kidney disease do not respond to commonly used drug treatments, especially in genetic disorders that affect the kidneys’ filtration system known as the glomerulus. With no available treatments for these children, improving our understanding of these diseases is critical to finding new therapies.

Improving understanding of kidney disease

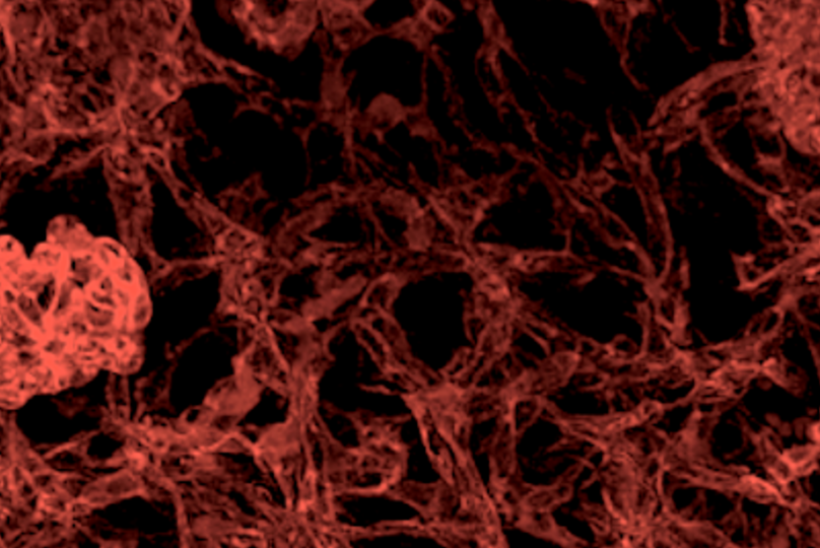

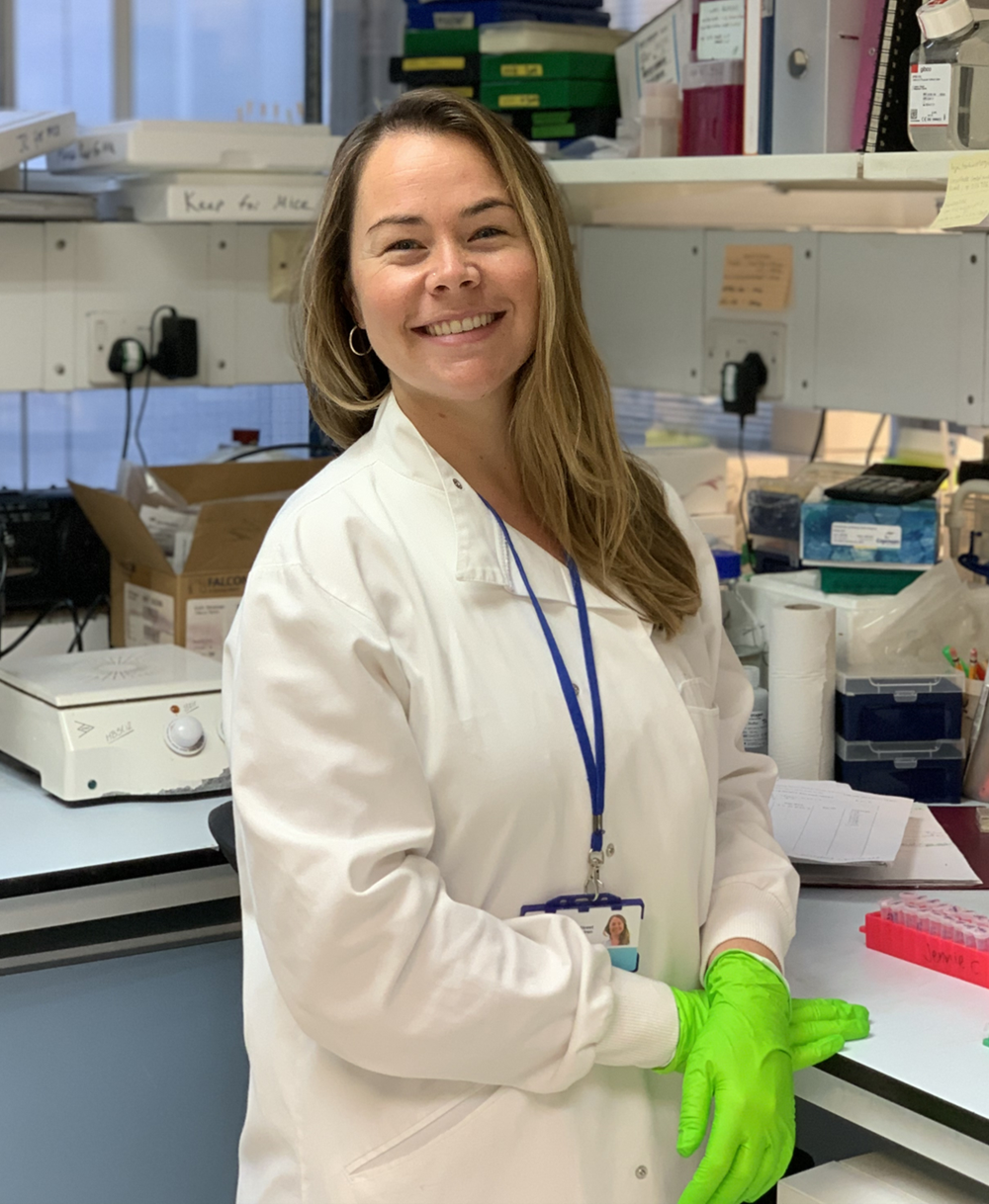

Dr Jennie Chandler has been working at UCL GOS ICH with a pre-clinical model of kidney disease in mice that carries a change in a gene called Wilms Tumour 1 (WT1), which is often linked with childhood kidney diseases that affect the glomerulus. Through this model, the research team closely studied how the disease progresses and how it changes the way the cells of the kidney glomerulus communicate with one another.

They found that the production of several signalling chemicals important for blood vessel health were disrupted in the glomerulus during the early stages of disease. These early changes were linked with a loss of glomerular blood vessels as the disease progressed. The health of these blood vessels is very important to supply the glomerulus with blood for filtration, allowing for the healthy production of urine.

Dr Chandler and the UCL GOS ICH team then worked with GOSH and the Hôpital Universitaire Necker‑Enfants Malades and found that blood vessel loss could also be seen in kidneys of patients with the same genetic changes in the WT1 gene.

Among the signalling chemicals that were disrupted, adrenomedullin was identified as important. The team monitored blood vessels cells in a dish and found that by increasing the levels of adrenomedullin, blood vessel health was improved.

This work has deepened our understanding of glomerular kidney disease linked to WT1 and has crucially identified an option to slow the damage to, and loss of, glomerular blood vessels.

Next steps will be to further investigate adrenomedullin and other signalling chemicals important for blood vessel health, as these could provide an alternative therapy for patients at risk of life altering kidney failure, potentially delaying the need for dialysis or transplantation.

The research has just been published in The Journal of Pathology.

Dr Jennie Chandler was supported in 2021 by an NIHR GOSH BRC Catalyst Fellowship and then went on to secure a Kidney Research UK Intermediate Fellowship and this work is a product of both of those fellowships. Dr Chandler is a member of the Junior Faculty at the NIHR GOSH BRC.

Jennie said: "This work has taken us a step closer to identifying new treatments for a currently untreatable childhood kidney disease. By adding to our understanding of how glomerular cells communicate in disease, we have found signalling pathways that can now be investigated as therapeutic targets. The project involved a great collaborative team at UCL GOS ICH and beyond, and would not have been possible without my Fellowship funding from the NIHR GOSH BRC and Kidney Research UK. I am now excited about next steps and taking this work further!".