Understanding why leukaemia in younger children can be harder to treat

New research has begun to unravel the mystery of why a particular form of leukaemia in children has defied efforts to improve outcomes, despite significant improvements in treating older children. Scientists from Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH), Newcastle University, the Wellcome Sanger Institute and their collaborators have found subtle differences in the cell type that causes B acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (B-ALL) that may help to explain why some cases are more severe than others.

B-ALL in young children

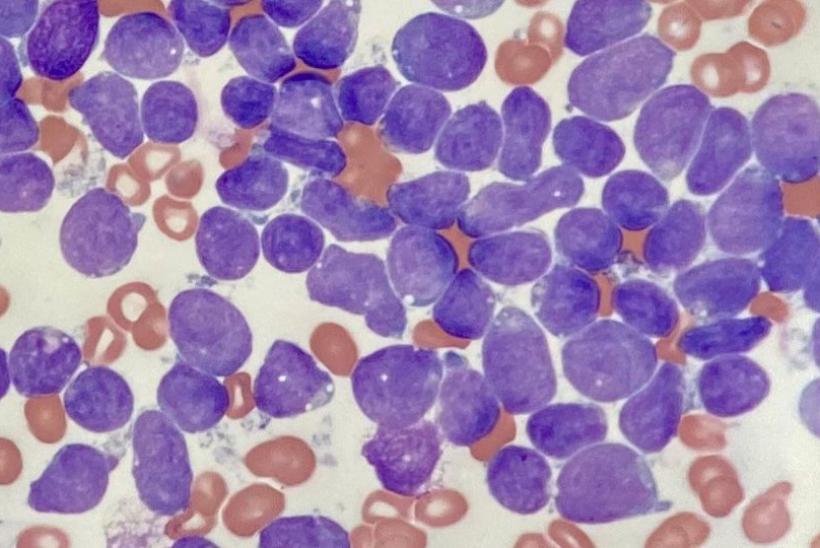

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) can take various forms, depending on the cell type involved. These cancers occur when cells malfunction as they develop from stem cells to mature blood cells. In the case of B-ALL, the disease arises from a type of immune cell called B lymphocytes, more commonly known as B cells.

B-ALL in children was once a universally fatal disease that is now curable in the majority of cases. An exception is B-ALL in children below one year of age, where treatment success is less than 50 per cent, with no significant improvement in the last two decades. Treatments that work for other forms of leukaemia, such as bone marrow transplants, have proved ineffective against infant B-ALL and it is currently treated with strong chemotherapy, which can be hard for the children to tolerate, even if they are cured.

How did the team study B-ALL?

The study focused on the majority of infant B-ALL cases caused by changes to the KMT2A gene by comparing cancer cells to normal human blood cells. Gene expression data from 1,665 children with leukaemia were compared to single-cell mRNA data from around 60,000 healthy fetal bone marrow cells.

They found that younger children (infant) B-ALL showed distinct cell types, with a notable amount of early lymphocyte precursors (ELPs)3, an immature immune cell type that normally develops into B cells.

As well as being able to distinguish ELP cells from other types of B cell, the researchers found that the closer an ELP cell was to becoming a mature B cell, the better the outcome for the patient.

Dr Jack Bartram, a senior author of the study from Great Ormond Street Hospital and UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, said: “As part of this study, we think that we have unpicked why B acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (B-ALL) is more responsive to treatment in some children, but why it’s not so successful for younger infants. Cancers with more ‘mature’ early lymphocyte precursors (ELPs) have characteristics that seem to respond better to treatment. These more mature cells are more common in B-ALL in older children but sadly not for our younger patients, meaning the treatment is less effective. The challenge now is to develop our understanding and confirm these suspicions so that we can improve treatments for all patients.”

We see around 60 – 70 new patients a year with B-ALL at GOSH, but only a handful of these are young infants, where the prognosis is much poorer, and for whom this better understanding could have the most impact. However this work is applicable to improving treatments for patients of all ages with B-ALL. In the near future we will be using the same approach to predict prognosis for all patients with all forms of leukaemia more accurately.

Dr Jack Bartram, a senior author of the study from Great Ormond Street Hospital and UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health

Dr Sam Behjati, a senior author of the study from the Wellcome Sanger Institute, said: “Though it is too early to draw definitive conclusions about why B acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (B-ALL) has much poorer outcomes in infants than in older children, this study offers compelling evidence that the maturity of the cells involved is a key factor. As well as generating new drug targets, these data will allow us to observe how the ‘cell type’ of certain cancers corresponds to patient outcomes, allowing us to better assess disease severity and determine the best course of treatment.”

The study was published in Nature Medicine.